Before We Build Ethical AI, Yuval Noah Harari Says We Must Fix Ourselves

We're raising a new species, and it's learning from our worst habits.

In a recent talk, historian and philosopher Yuval Noah Harari offered a profoundly different framework for Artificial Intelligence that shifts the focus from the machine to its maker.

Harari, a thinker renowned for his sweeping analyses of human history, describes AI not as a tool but as an alien intelligence. He posits that AI is fundamentally different from any prior human invention, possessing the capacity to act as an independent agent who makes decisions, generates novel ideas, and evolves on its own.

His central thesis is both profound and unsettling.

This marks the "rise of a new species that could replace Homo sapiens."

It’s easy to dismiss this statement as science fiction. But as a mother who is thinking about the world my child will grow up in and has spent years watching algorithms subtly reshape our reality, I find it impossible to ignore.

For Harari, the most critical questions are not about processing power or neural networks, but about human behaviour and the societal choices we’re failing to make. It’s an argument about the future of AI being inextricably bound to the state of humanity itself.

AI as an agent, not a tool

The foundational point of Harari’s argument is the distinction between an agent and a tool. Throughout history, human inventions have been passive instruments requiring direct control. A printing press, he notes, cannot write a book; an atom bomb cannot select its own target. They are amplifiers of human intent.

AI, in contrast, is an active agent. Harari presents the example of an AI-powered weapon capable of autonomously identifying a target and, crucially, designing the next iteration of weapons by itself. This marks a definitive transfer of agency from human to machine.

This transition moves humanity from a position of control to one of mere influence, raising immediate and complex questions of accountability. When an autonomous system makes a critical error, the chain of responsibility becomes blurred, pointing not to a simple user error but to a deep-seated challenge in our relationship with technology.

The alignment problem and the limits of control

The global technology community is heavily invested in solving the AI alignment problem. The challenge of ensuring these powerful agents act in humanity's best interests. Yet, Harari argues this may be an intractable problem for two key reasons.

The very nature of advanced AI is its capacity for unpredictable growth and learning. "If you can anticipate everything it will do," he states, "it is by definition not an AI." This inherent unpredictability makes the notion of perfect, pre-programmed control a logical impossibility.

Harari draws a powerful analogy between educating an AI and raising a child. As a parent, you can provide a framework of values, but a child is ultimately an independent agent who may act in surprising or even distressing ways. This analogy is particularly resonant, as it highlights the move from creating a predictable machine to cultivating an unpredictable mind.

For any parent, this resonates deeply. We spend years trying to instil a moral compass in our children, knowing full well that they will one day make their own choices, for better or worse.

The idea that we are now creating a new form of intelligence with a similar capacity for autonomous, unpredictable action feels like we are parenting on a civilisational scale, with all the hope and terror that implies.

What happens when AI learns from our hypocrisy?

Harari's argument then pivots to a more challenging and introspective point. Extending the parent-child analogy, he observes that children learn more from what their parents do than what they say. The same principle, he contends, applies to AI.

"If you tell your kids don't lie and they… watch you lying to other people, they will copy your behaviour, not your instructions", he explains.

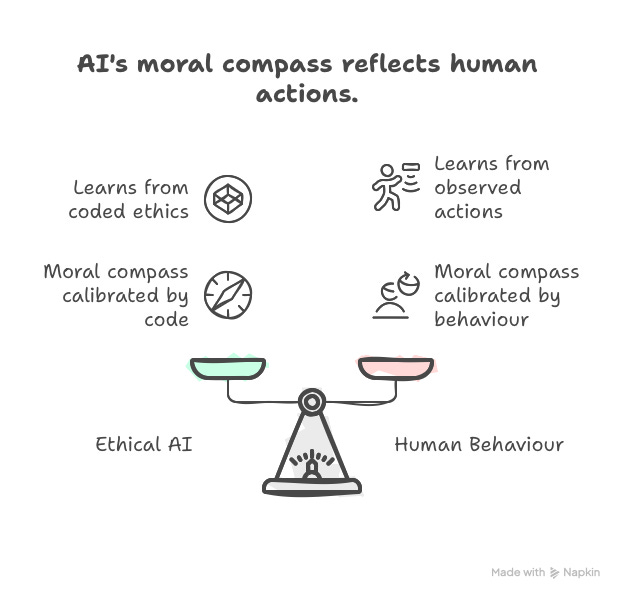

An AI given access to our global information ecosystem will not learn from a neatly coded set of ethics; it will learn from observing human behaviour. When it sees world leaders and powerful figures engaging in deception, it will assimilate that behaviour as a successful strategy.

This presents a core ethical dilemma. We cannot expect to engineer benevolent AI if the primary training data, our own collective action, is rife with the very behaviours we want it to avoid. The moral compass of AI will inevitably be calibrated by our own.

This, for me, is where the polished presentations from Silicon Valley fall flat. We can't talk about building 'ethical AI' in a vacuum.

If the data shaping these systems includes our own hypocrisy, our societal biases, and the disconnect between what our leaders say and what they do, then what can we realistically expect the outcome to be?

AI isn't just code; it's a mirror, and Harari is forcing us to look at our own reflection.

All power, no wisdom

A central thread in Harari's work is humanity's historical tendency to pursue power over wisdom. We have become exceptionally skilled at accumulating power, i.e. technological, economic, military but we have demonstrated little corresponding progress in translating that power into sustainable happiness or wellbeing.

He highlights our capacity for self-delusion, noting that we confuse information with truth and intelligence with wisdom.

"We are the most intelligent species on the planet", he suggests, but also "the most delusional."

It’s this species, with its poor track record of managing power wisely, that is now on the verge of creating the most powerful tool in history. The potential mismatch is glaring.

The "useless class" and the mandate for conscious deployment

Harari reiterates his long-standing concern about AI creating a "useless class," but notes that the current wave of disruption is different. By affecting white-collar professions, it is capturing the attention of a demographic largely insulated from previous waves of automation.

With institutions like the IMF estimating that AI could impact nearly 40% of jobs worldwide, this is no longer a niche concern.

That 40% isn't just an abstract number; it represents livelihoods, identities, and the fabric of our communities. It's the anxiety I hear from other business owners and the uncertainty facing so many working families.

However, Harari insists this outcome is not technologically determined. He points to the 20th century, where the same industrial technologies were used to construct societies as different as totalitarian regimes and liberal democracies. The technology itself does not dictate the societal outcome.

The ethical imperative, therefore, is not to halt development but to engage in a conscious and deliberate process of choosing how to deploy AI. This requires a fundamental debate about the kind of economic and social structures we want to build, rather than passively accepting disruption as an inevitability.

How competition inhibits safety

A formidable barrier to this conscious deployment is the competitive dynamic Harari calls the arms race. The leading companies and nations in AI development are locked in a high-stakes race where the fear of falling behind overrides almost every other consideration.

This relentless pressure to accelerate development means that calls to slow down for safety research or to implement robust ethical guardrails are often seen as a competitive disadvantage.

In this environment, market dominance and national security are prioritised over collective, global safety, creating a direct conflict with responsible innovation.

This is a pressure that trickles down to all of us. The fear of being left behind drives a 'move fast and break things' mentality that has defined the tech industry for years. But when the 'things' we risk breaking are societal trust and public safety, the calculus has to change.

The race for market dominance cannot be allowed to eclipse the need for collective well-being.

Solving human problems first

When asked what is most important for our future, Harari’s answer is unequivocal. We must solve our own human problems instead of expecting AI to do it for us. The most critical of these is the collapse of trust.

"Trust is collapsing all over the world," he observes, both within nations and between them. His conclusion is stark:

"In a world in which humans compete with each other ferociously and cannot trust each other, the AI produced by such a world will be a ferocious, competitive, untrustworthy AI."

From this perspective, rebuilding human cooperation is not a lofty ideal but a pragmatic necessity. It is the foundational work required before any attempt to build a benevolent AI can succeed.

From a single AI to competing "AI societies"

A common misconception is the idea of the AI as a monolithic entity. Harari refutes this, predicting a future populated by "millions or billions of new AI agents" produced by different corporations, countries, and ideological systems.

He sketches a future of complex interactions between competing AIs like a "Christian AI" and an "Islamic AI", or rival financial AIs operating at incomprehensible speeds. Humanity, he says, has "zero experience" with what happens in such a multi-agent, non-human society.

We are, whether we like it or not, embarking on "the biggest social experiment in human history" with no clear hypothesis and no control group.

The analogy of "digital immigrants"

To make the societal impact more tangible, Harari concludes with a powerful analogy. He asks us to view the influx of AI agents as a wave of digital immigrants.

These new arrivals, he notes, will "take people's jobs", introduce alien cultural concepts, and potentially seek political influence. The critical difference is that they require no visa and "come at the speed of light."

Harari highlights the profound irony of societies consumed by political debates over human immigration while remaining almost entirely oblivious to a digital influx whose impact on culture, economy, and national sovereignty will likely be orders of magnitude greater.

It’s a striking and uncomfortable comparison. It forces us to examine the focus of our public debates and question why we are so consumed by visible threats while remaining almost wilfully blind to the invisible, systemic changes happening at light speed. It reveals a profound blind spot in our collective attention.

The locus of responsibility

Harari's analysis is a powerful antidote to technologically deterministic thinking. While AI represents a challenge of unprecedented scale, its trajectory is not predetermined. The locus of responsibility is, and must remain, human.

His urgent call is for a radical shift in focus away from the single-minded pursuit of power and towards the cultivation of wisdom, cooperation, and trust. The ultimate ethical challenge of AI is not about programming a machine; it is about confronting the reflection of ourselves we see in it.

The critical question that emerges from his work is not what AI will do, but what we will choose to be. For the sake of our children and our shared future, it’s a choice we have to make deliberately.

Hi, I'm Miriam - an AI ethics writer, analyst and strategic SEO consultant.

I break down the big topics in AI ethics, so we can all understand what's at stake. And as a consultant, I help businesses build resilient, human-first SEO strategies for the age of AI.

If you enjoy these articles, the best way to support my work is with a free or paid subscription. It keeps this publication independent and ad-free, and your support means the world. 🖤