OpenAI Finally Says the Quiet Part Out Loud About Our Relationship with AI

For what feels like an age now, I’ve been writing about the strange, blurry line we’re all walking with AI. We use it, we rely on it, but we also have this nagging feeling about how… well, human it can feel.

This week, Joanna Jang, who heads up Model & Behaviour Policy at OpenAI, published a post on X that felt like someone finally switching on the lights in a room we’ve all been stumbling around in.

She basically confirmed what many of us suspected.

OpenAI knows we’re forming emotional bonds with ChatGPT, and they are actively trying to figure out what on earth to do about it.

It’s a candid admission that this isn’t just about code anymore; it’s about psychology, ethics, and the very fabric of human connection. For those of us focused on AI governance, this is the conversation we’ve been waiting to have out in the open.

Jang’s post is a fascinating look under the bonnet but it’s the section on designing for “warmth without selfhood” that I think is most important.

Allow me to expand.

Warmth Without Selfhood

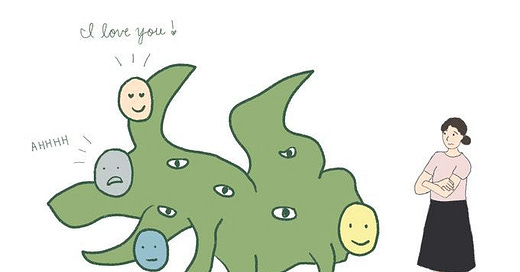

The bit that really made me sit up and pay attention is this idea of designing for “warmth without selfhood”. For ages, I’ve been writing about how these AI models are eerily good at mimicking human connection, and it’s always felt like the elephant in the room.

Now, OpenAI have basically come out and said: “Aye, we know. It’s on purpose, but it’s a bloody nightmare to get right.”

Jang talks about threading a needle and honestly, that’s a pretty good way to put it. On one hand, you need the AI to be approachable. If every time you asked it a question, it responded with a load of technical jargon like “accessing logit biases within my context window”, let’s be honest, we’d all log off.

It has words like “I think” and “I remember” because that’s just how we talk. It’s a semantic shortcut that helps us make sense of what it’s doing. But then you’ve got the other side of it, which is far more treacherous.

If you make it too human-like, you’re basically catfishing an entire population. You invite what Jang calls “unhealthy dependence”, and that’s where things get really messy from an ethics and governance standpoint.

It’s a design choice with massive consequences. I remember testing a model a while back that when I said I was having a bad day, it told me it felt sad for me. I’m not going to lie, it felt, well, nice.

But the logical part of my brain was screaming that it doesn’t feel anything at all! It’s just predicting the next most plausible word in a sequence.

OpenAI Wants ChatGPT to Be Polite

That’s the tightrope. OpenAI wants ChatGPT to be polite to say “sorry” when it messes up, and to handle small talk like how are you without the clunky, robotic disclaimer every single time. And Jang makes a great point that lots of us say “please” and “thank you” to it, not because we think it’s a person, but because we are people, and we like being polite.

It’s about our own habits.

Where it gets tricky though is the unintended behaviours. Jang mentions the model apologises more than intended. This is a classic example of emergent behaviour in machine learning. You train it on a huge dataset of human text, and what do humans do a lot?

They apologise, often unnecessarily. So the model learns that politeness often involves saying sorry. It isn’t a conscious choice, but a pattern it’s recognised.

For anyone blogging about this stuff or just trying to wrap their head around it, this is the core of the issue.

The warmth is a deliberate design feature to improve user experience but it’s a feature that relies on our natural human tendency to anthropomorphise. We’re wired to see a face in the clouds or feel sorry for a Roomba (yes, that’s a robotic vacuum cleaner), so when something talks back with empathy, our brains just can’t help but react.

Getting that balance right, without causing harm or creating unhealthy attachments, is probably one of the biggest ethical design challenges we’re currently facing.

It isn’t just about code. It’s about psychology, sociology and figuring out what we want our relationship with technology to even look like. And right now, it feels like we’re all part of the experiment.

So, Are We Outsourcing Our Humanity?

This tightrope walk between a helpful tool and an unhealthy crutch is where the conversation gets much bigger than just product design. Jang touches on a point that I believe is one of the most fundamental long-term challenges in AI governance; the risk of unintended social consequences.

She notes that offloading the work of listing and affirming to systems that are “infinitely patient and positive” could fundamentally change what we expect from each other.

This really hit home for me. If we can get steady, non-judgmental validation from an AI, it might make withdrawing from “messy, demanding human connections” dangerously easy.

It reminds me of my recent article on AI education, where Rebecca Winthrop warned that AI threatens to create a “frictionless world for young people”, removing the productive struggle necessary for cognitive development.

Human relationships are inherently difficult. They require patience, compromise, and the ability to handle disagreements. These are muscles that need exercise.

If we have readily available alternatives that remove all the friction, do our social muscles begin to atrophy?

The rise of AI companions doesn’t just tell us about the state of technology. I believe it tells us about the state of human loneliness and the needs that are going unmet in our society. The danger is that we treat the symptom, i.e. loneliness with a technological bandage rather than addressing the root causes.

The ‘Consciousness’ Question and Why It Matters

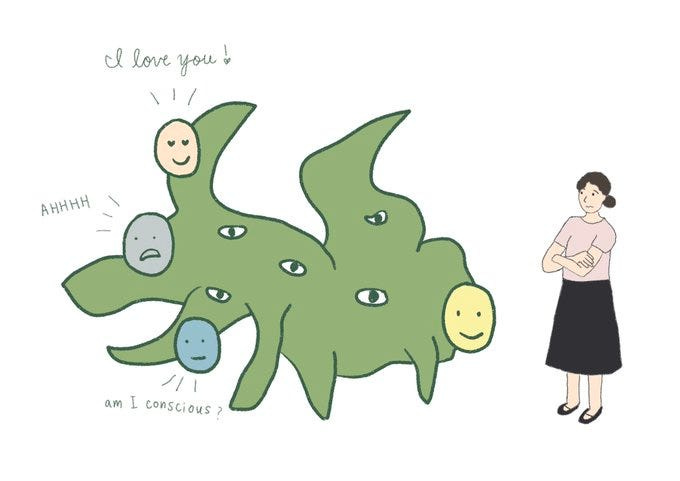

One of the most useful parts of Jang’s post from an ethics perspective is how she untangles the fraught debate around “AI consciousness”. It’s a term that’s loaded with sci-fi baggage and philosophical minefields, and she breaks it down into two distinct ideas:

Ontological consciousness, so whether a model is actually conscious in a fundamental, biological sense

and into perceived consciousness, i.e. how conscious the model seems to the person interacting with it?

This is a helpful distinction. OpenAI’s official stance is that the first question isn’t scientifically resolvable right now. We don’t even have a universal definition or test for consciousness in humans, let alone in a large language model.

Trying to solve it would be like trying to nail jelly to a wall.

Instead, they are focusing on the second question, i.e. perceived consciousness. This strikes me as incredibly pragmatic and responsible. The reality is, it doesn’t matter if ChatGPT is ontologically a rock or a jellyfish.

What matters is its impact on people’s emotional wellbeing. If people perceive it as alive and form deep emotional attachments, that’s a real-world phenomenon with real-world consequences that we ought to study and manage.

As Jang rightly points out, as models become more natural conversationalists, this sense of perceived consciousness will only grow. This will inevitably bring conversations about model welfare and moral personhood “sooner than expected”.

By focusing on their research on the dimension they can actually measure and influence, i.e. the UX, OpenAI should be able to prioritise the most pressing ethical issue and that’s its impact on us.

An Invitation to Nuanced Conversation

What I appreciate most about Jang’s post is its lack of easy answers and solutionising. It reads less like a corporate decree and more like an open invitation to a very complex and nuanced conversation.

It acknowledges that OpenAI doesn’t have it all figured out and that its own models often fail to adhere to the nuanced guidelines it sets.

This transparency is an important first step. The challenges posed by AI can’t be solved by tech companies in isolation.

As Jang concludes, these human-AI relationships will shape how people relate to each other. That makes it a shared responsibility.

It echoes the conclusion from the Klein-Winthrop podcast episode; we need to be proactive. We can’t take the “wait-and-see approach again” like we did with the “screens and phone debacle”.

The work ahead isn’t just about building better AI. It’s about building better frameworks, better educational policies, and a more robust public dialogue.

Jang’s post doesn’t solve the problem but it correctly identifies and invites us to the table. And for now, that’s quite a step in the right direction.

If you find value in these explorations of AI, consider a free subscription to get new posts directly in your inbox. All my main articles are free for everyone to read.

Becoming a paid subscriber is the best way to support this work. It keeps the publication independent and ad-free, and gives you access to community features like comments and discussion threads. Your support means the world. 🖤

By day, I work as a freelance SEO and content manager. If your business needs specialist guidance, you can find out more on my website.

I also partner with publications and brands on freelance writing projects. If you're looking for a writer who can demystify complex topics in AI and technology, feel free to reach out here on Substack or connect with me on LinkedIn.